Active retail traders are important to keep liquidity relatively high in Thai small-cap stocks

The extent to which different categories of market participants contribute to liquidity and price formation on a stock exchange depends on a complex set of factors, which include (but are not limited to) regulatory, institutional and cultural features. For example, while in continental Europe individual investors hardly trade directly on the stock market, the opposite holds in many Asian countries, where retail investors do actively access the market to trade in stocks, thus sustaining local stock market liquidity. In particular, retail investors are an important category of market participants for the Stock Exchange of Thailand (SET), a market that has invested a lot in financial literacy and other interventions aimed at attracting retail participants (see WFE retail investors’ report here), and has managed to obtain a balanced participation across different investors’ categories (see WFE international investors’ report here). As previous research of ours has found (see WFE report on market liquidity in emerging markets here, and an academic contribution on the topic here), a balanced participation is a good way to obtain satisfactory stock market liquidity and limit price fluctuations.

In this article we put a magnifying lens on stock market participation and liquidity on SET, exploiting unique proprietary timestamped trading data kindly provided by the exchange. Our database contains all submitted orders and executed trades that took place on the market over the course of April 2018 for a sample of 100 stocks. This rich database contains information on the category those investors who submitted an order or executed a trade belong to, thus allowing us to estimate the extent to which different market participants (i.e. retail, domestic institution and foreign institution) contribute the most to trading activity on the market.

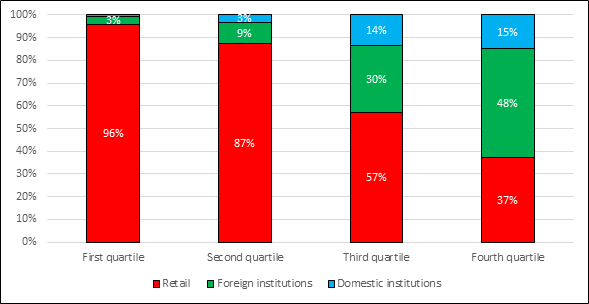

As mentioned, SET is a retail-dominated exchange, though participation of individuals is not uniform across stock sizes. While trading in small and smaller mid-cap stocks is indeed overwhelmingly dominated by retail investors, we observe that trading in larger mid-cap stocks is more balanced between the three categories, while trading in large stocks is largely performed by foreign and domestic institutions. Figure 1 below describes market participation broken down by quartiles of market capitalisation over the sample period.

Figure 1: Market participation per quartile of market capitalisation

Individual traders on SET are fairly active, leading to relatively high levels of trading activity in small and medium cap stocks. Table 1 shows average daily trading activity over the sample period, broken down by quartiles of market capitalisation, together with additional descriptive statistics:

Table 1: Liquidity indicators per quartiles of market capitalization (means)

|

|

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

|

|

Quartile 1 |

Quartile 2 |

Quartile 3 |

Quartile 4 |

|

Daily trading volume |

18.82 |

12.65 |

31.26 |

55.41 |

|

Daily trading value |

32.21 |

36.05 |

164.25 |

1,255.03 |

|

Turnover velocity |

479% |

189% |

144% |

144% |

|

Effective spread |

59.62 |

37.11 |

32.96 |

24.99 |

|

Price impact |

36.76 |

30.29 |

24.84 |

20.36 |

|

Realised spread |

23.23 |

6.82 |

8.13 |

4.61 |

|

Observations |

111,379 |

152,107 |

484,914 |

1,302,449 |

Daily value traded: million Bahts. Daily volume traded: millions of units. Turnover velocity: percentage. Calculated as (Daily trading value x 245)/Market capitalisation. Effective spread, realised spread and price impact: Basis points.

As evident from the table, large cap stocks see disproportionately more daily Baht turnover than small-cap stocks. The average daily trading value for stocks in the fourth quartile of market capitalisation is 1.25 billion Baht, more than 30 times the trading value for stocks in the first quartile, amounting to 32.21 million Baht. This result is, however, driven by the higher prices of large cap stocks, as small- and mid-cap stocks see overall comparable trading volumes to large-cap stocks. For example, the average daily volume traded for stocks in the fourth quartile of market capitalisation is 55.41 million units, only 2.9 times larger than the average daily volume for stocks in the first quartile, amounting to 18.82 million units. This is because retail investors trade uniformly across all stock sizes, while institutional investors are mostly interested in large cap stocks, as evident when comparing retail volume between first (96% x 18.82 = 18) and the 4th quartile (37% x 55.41 = 20). In addition, it must be noted that the (total) Baht value traded in small stocks is large as compared to the size of the companies: turnover velocity (the ratio between the monetary value traded and the respective market capitalisation, a commonly used measure of liquidity) is indeed higher for small- and mid-cap stocks than it is for large stocks. For example, the average turnover velocity for stocks in the first quartile of market capitalisation is 52%, as opposed to 12% for stocks in the fourth quartile. These results show that the equivalence small stocks/little trading, a fair description of how markets function in many exchanges in the EMEA and Americas region does not apply to the Thai market.

As evident from Table 1, though, looking at turnover velocity only would give a misleading picture of liquidity on the stock exchange. For example, looking at the effective spread (a commonly used indicator of the adverse selection cost paid by liquidity demanders), it is immediately evident that it is monotonically decreasing in stock size, with the average effective spread for stocks in the first quartile of market capitalisation being almost 60 Bps, and the corresponding figure for stocks in the fourth quartile of market capitalisation being almost 25 Bps (2.4 times smaller). This implies that potentially informed traders demanding for immediate execution face much higher hidden costs when trading in smaller cap stocks than when trading in larger cap stocks. Consistently, trades in small cap stocks have higher price impacts than trades in large cap stocks, hinting that smaller cap stocks are characterised by lower price efficiency: the average price impact of trades in the first quartile of market capitalisation is almost 37 Bps, and the corresponding figure for stocks in the fourth quartile of market capitalisation is roughly 20 Bps (more than three times smaller). As effective spreads are higher than price impacts for all company sizes, liquidity suppliers enjoy positive profits (the realised spread) across all the sample, with the average realised spread being monotonically decreasing in market size, another hint that smaller cap stocks are characterised by higher frictions.

While small cap stocks appear to be relatively more illiquid when looking at spread measures, it must be noted that spreads are overall comparable across different stock sizes, thanks to the already emphasised high levels of trading activity in small cap stocks, and to a tick size sliding scale proportional to stock prices, a market structure feature that keeps spreads overall uniform across different stock price levels. We therefore conclude that active retail traders are important to keep liquidity relatively high in Thai small-cap stocks. However, we caveat that both trade and spread measures of liquidity should be analysed to gauge a complete picture of how liquidity is distributed on SET, and ideally on any other market.