How the U.S. SIP really works

The U.S. Securities Information Processor (SIP) is often considered the example for market data around the world. But how does it really work?

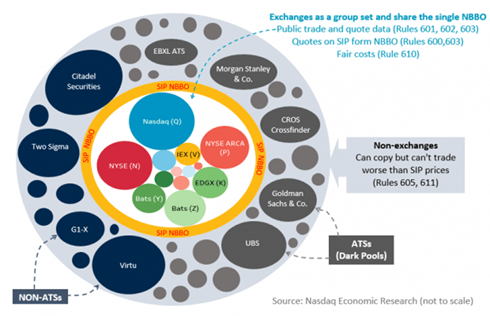

U.S. stock markets have 16 different exchanges, all competing to quote and trade each stock. There are also around 30 dark pools (ATSs) and numerous single-dealer platforms that match trades off exchange.

The SIP effectively stitches all that fragmentation back together. It mandates the consolidation of best prices across all 16 exchanges in the U.S. market (the NBBO).

Chart 1: The SIP creates guardrails for all executions to protect investors

The data collected is also the data required for trading

There is an important link between the data the SIP collects and the data required to meet trading rules. The NBBO prices are also protected (Rule 611), meaning the SIP is used to limit locked and crossed markets (Rule 610). The NBBO is also used to measure execution performance of “covered” orders (Rule 605). Off-exchange trades can’t happen worse than exchange prices, protecting investors.

All other data, including quotes that are away from the market, is optional and taken by relatively few, mostly sophisticated subscribers.

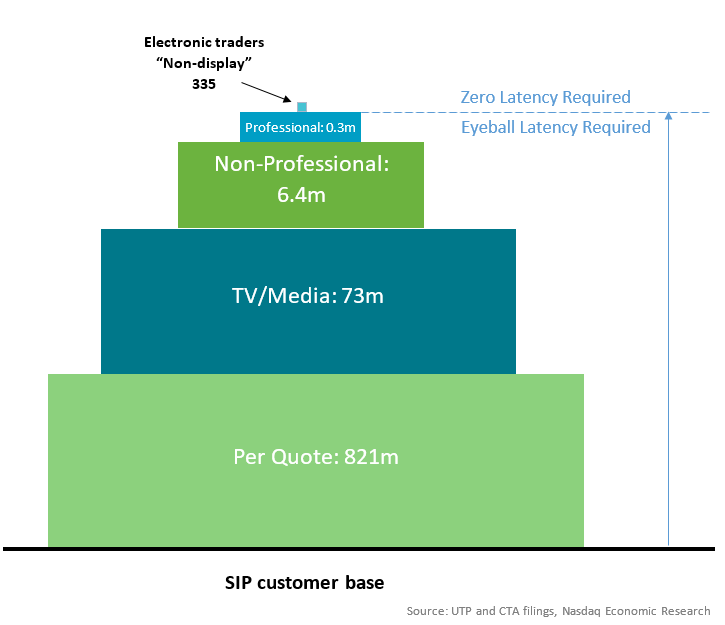

It’s impossible to be fast enough to pre-trade for all

By definition, as the SIP is protecting quotes and trade-throughs, it is a pre-trade data source. That makes latency important.

Over the last decade, the U.S. SIP has improved how fast it compiles all the data from a 6 millisecond (ms) to a 0.015ms delay. Those improvements are undetectable to “human” traders, but are still not fast enough for some automated traders.

No matter how fast you make data, it is always delayed when it gets to consumers. And if you want a single reference price for all users, you add additional geographic latency. It’s just physics.

Regulators in the U.S. have recently suggested the only way speed the SIP up is by allowing anyone to compile their own BBO, forgoing the single “N”BBO that investors and the public prize.

Chart 2: The more sophisticated SIP customers get, the less of them there are to share additional costs

Although the SIP is good for the public, it’s not a public good

U.S. regulators never set out to make data “free;” quite the opposite.

They realized that the SIP would make markets better if it made markets more transparent. To that end, the SIP set out to:

-

Reward those for contributing to “good” transparent markets via NBBO prices and all trades.

-

Charging those who consumed it.

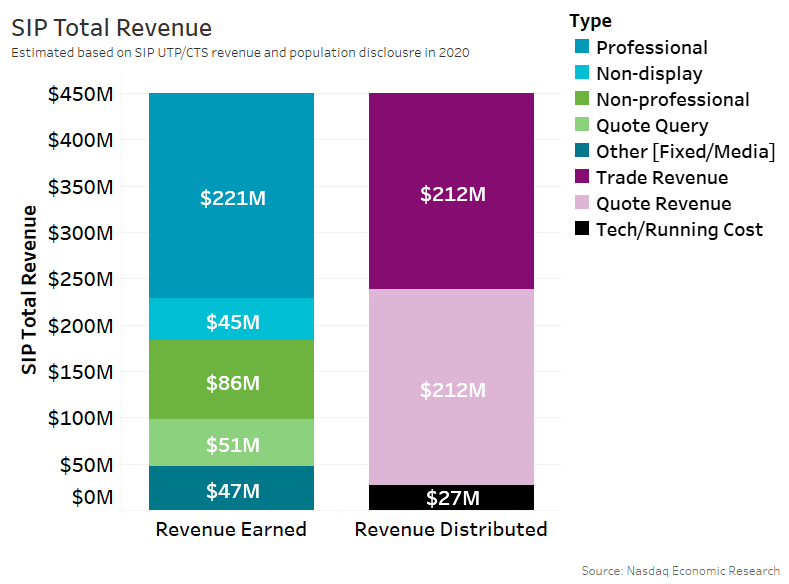

Data shows that all the different consumers contribute to a SIP revenue pool of around $400 million each year, and that is mostly distributed back to those providing the best data to the SIP. Although that might seem like a lot, U.S. market liquidity is over $120 trillion each year. That’s a cost of just 0.00035% per dollar traded, which is a fraction of the spread-cost on the most liquid U.S. stocks (currently at 0.01%).

Based on SEC estimates in the NMS-II plan approval, we estimate that tech and operating expenses are around 6% of total SIP cash flows.

Chart 3: SIP revenues charged to users are then reallocated, mostly to reward transparent markets

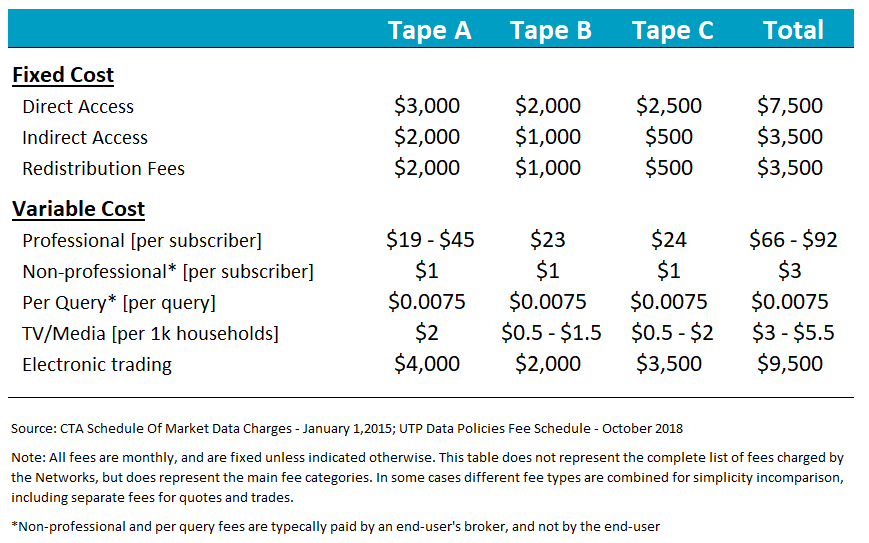

SIP revenues come from a use-case-based rate sheet

Some users make large profits from data (some by trading a lot, others by not trading at all). Many others earn no income from it at all, even if it is critical to valuing portfolios or managing risk. The SIP offers a menu of per-user charges based on usage patterns:

-

Per query rate of $0.0075: representing a cost of around 0.008 basis points (bps) on the average $10,000 trade.

-

Monthly rate for retail of $1/tape: For “non-professionals” that trade much more.

-

TV and media pay 0.5-cent/month: per user, with millions of “eyeballs” paying them via advertisements.

-

Professional investors have a monthly rate of around $90 for all tapes: Professionals include broker dealers and investment advisors, who earn significant profits on client trades.

-

Computers trading pay around $9,500/month: Given computers can work the trades of many customers at once, it makes sense that algorithms pay the most for SIP data.

Table 1: SIP monthly rate sheets charge different users based on their expected usage of the data

SIP returns revenues to those providing NBBO and trades

If we are trying to reward market “goods,” how should that work?

The SIP does this with an elegant (but complex looking) formula that:

-

Rewards quotes and trades equally, a sign that off-exchange trades add to price discovery also.

-

Reward liquidity more, where deeper-valued quotes or trades earn a greater share of SIP revenues than small trades and quotes.

-

Help less liquid stocks count more, to partly offset their immaterial contribution to liquidity.

-

Ensures flickering quotes don’t count.

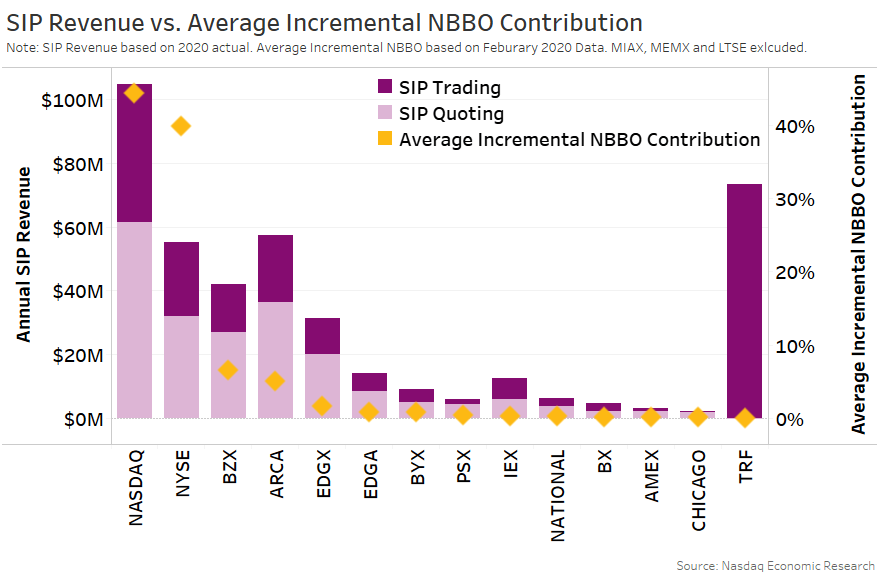

What you end up with is an allocation of SIP revenues to trading venues that roughly corresponds to how much trading is done, not how much the venue improves investor outcomes.

Chart 4: SIP revenue allocations compared to quote quality

Unintended consequences and resource misallocation

There are still examples where the SIP fails to efficiently allocate resources.

It is widely agreed that it subsidizes fragmentation. By rewarding all marginal quotes and trades equally, there is no accounting for fixed costs or complexity caused by additional venues.

Market forces also currently result in most of the $73 million in “TRF” revenues (for off-exchange trades) being returned to off-exchange venues. We estimate these revenues more than cover those venues’ costs for exchange data.

But the best example of market failure might be the fact that the SIP provides data revenues to some exchanges who can’t even give their proprietary data away.

What does this mean?

Although the U.S. SIP is the envy of the world, it is not without its problems.

In the process of creating a single NBBO, it introduced geographic latency. That’s a problem because the NBBO also protects quotes, making it a pre-trade data feed.

Importantly, the data the SIP collects is also required for trading and execution quality metrics, while other data is optional, with a relatively low number of sophisticated subscribers.

Finally, even though the SIP tries to set its economics in a way designed to make markets better, and more transparent, it sometimes does the reverse—encouraging fragmentation and dark trading at the expense of competition for public quotes.

Despite what the rest of the world thinks, the U.S. SIP is far from perfect.